Interview with Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng, United Nations Special Rapporteur on the right to health

In her latest report to the United Nations General Assembly, Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng emphasises that health workers and carers are not only providers of medical services, but also defenders of the right to health. Furthermore, she insists that the right to health is essential for achieving sustainable development goals.

Who is Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng?

Dr. Tlaleng Mofokeng is a passionate advocate for the right to health. Trained as a physician, she works on issues related to universal health coverage, sexual and reproductive health, HIV prevention, and menstrual health. She also advises national and international institutions.

The interview was conducted by Matilde De Cooman, policy and campaign coordinator at Viva Salud.

Healthcare workers as advocates for rights

Matilde De Cooman: Dr Mofokeng, thank you very much for joining us today. Let's get straight to the point. In your latest report, you emphasise the role of health workers and carers. Why do you see them as defenders of the right to health?

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng: We must view healthcare workers and carers as defenders and protectors of the right to health, in the same way that we understand journalists to be promoters of freedom of expression. When we say that journalists safeguard this freedom, everyone understands what that means. I make the same argument for healthcare workers and the right to health.

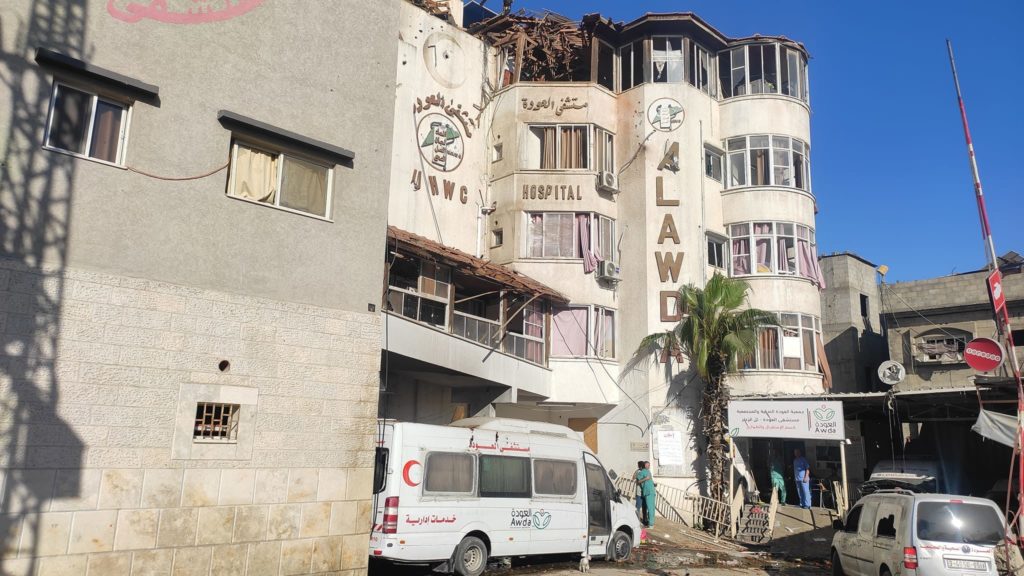

In places such as Sudan, Congo, Syria, Burma and other contexts of ongoing conflict, healthcare workers are the ones who stay and are the last to leave. Their mere presence illustrates why they must be recognised as defenders. We are seeing this tragically now in Gaza: when health workers choose to stay with their patients despite evacuation orders, they themselves become targets of harassment, enforced disappearance, torture, and even murder.

This report is important because it brings together the many stories of what healthcare workers have gone through and are still going through. As representatives of the Hippocratic Oath, we (doctors) are often dehumanised precisely because of this oath. It is as if, by choosing this profession, it becomes normal or expected that we constantly sacrifice ourselves. But governments also have a responsibility. Healthcare workers have families too, and every act of «expected sacrifice» has consequences for them as well.

In places such as Sudan, Congo, Syria, Burma and other contexts of ongoing conflict, healthcare workers are the ones who stay and are the last to leave.

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng

Patients recover in the same environments where healthcare workers must work. The right of healthcare workers to a safe and dignified working environment is inseparable from the right of patients to a healing environment. Both are important. When patients complain that the food is poor, that the roof contains asbestos, or that the linen is dirty, these are reflections of the staff's working environment. Advocating for patients therefore also means advocating for the rights of those who care for them.

That is why the report uses a human rights framework to call on UN Member States to recognise that the rights of health workers and carers are fundamentally labour rights: remuneration, migration, training, programmes and teaching methods. If governments treat health workers well, they are then able to protect and promote the rights of patients.

We must recognise that health workers are much more than providers of medicines or diagnoses. They are defenders of human rights. Their work is to protect and defend access to health; and their labour rights must be protected and promoted in the same way. I hope this report will help healthcare workers and carers to have a human rights basis for claiming labour rights, equity in the workplace and building global solidarity.

Matilde De Cooman: You mentioned the situation of health workers in Gaza. How do you see the role of UN experts in the face of these horrific attacks on the right to health?

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng: Shortly after 7 October, my colleague Francesca Albanese and I were among the first to clearly state that what we were witnessing was part of a larger genocidal pattern. We were among the first to call it what it was: genocide. At the time, many people were uncomfortable with this, but it had to be said. Later, the case before the ICJ unfolded and the evidence became clear to everyone. For me, the responsibility of this mandate goes beyond analysing events after they occur. It is about preventing violations in the first place. Too often, the UN commemorates instead of preventing.

From the outset, the genocide has targeted the right to health. It systematically destroys people's ability to access healthcare by attacking the underlying determinants of health such as water, electricity, fuel and food.

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng

From the outset, the genocide has targeted the right to health. It systematically destroys people's ability to access healthcare by attacking the underlying determinants of health such as water, electricity, fuel and food. Long before the world paid attention to the number of journalists killed, hundreds of healthcare workers had already been killed, yet their deaths were barely reported.

As a child who grew up under apartheid in South Africa, I was a teenager when Nelson Mandela was released from prison. My deepest childhood memories are therefore rooted in the anti-apartheid struggle and work. For me, the work I was doing on Gaza through the UN was not an academic exercise – it was rooted in the trauma I experienced as a child. Reliving and re-watching this, when I thought I would never have to do it again in my life, and doing it now through the UN in this way, was deeply personal.

The right to health and power structures

Matilde De Cooman: In your reports, you also emphasise the role of racism, colonialism and power structures in shaping health outcomes. Why are these factors so often overlooked in discussions about the right to health?

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng: From the outset of my term, I believed it was essential to adopt an anti-colonial and anti-racist framework to explain why the right to health remains unfulfilled in so many parts of the world. Many people still struggle to understand how coloniality and racism shape healthcare systems and influence the needs of communities that are ignored.

A key part of this is the idea of substantive equality. Substantive equality goes beyond the idea of treating everyone the same. It requires analysing power, how it works, and how it shapes access to rights. Substantive equality is based on human rights principles such as non-discrimination, meaningful participation and accountability. All these elements are essential for advancing the right to health. Many global systems, including global health, remain built on colonial and imperialist foundations, continuing to determine whose lives are valued, whose health is protected, and whose rights can be denied.

Matilde De Cooman: How do systems of racism affect the fight for the right to health today?

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng: What concerns me today is that ideas that were once hidden or unexpressed are now being expressed openly. I have long wanted to use the word «fascism» in my reports to the UN, but there has been resistance to this. Yet we can see it clearly: political leaders can say things without reflection or restraint, and many world leaders no longer understand their role as one of protecting people or creating societies where individuals can flourish.

People are not voiceless or powerless – it is the system that chooses not to see or hear them.

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng

Because I am a pro-choice advocate and work on the decriminalisation of sex work and transgender rights, I have always been positioned on the periphery of politics. Policies such as the Global Gag Rule (a US policy that reduces funding for organisations involved in abortion-related services) have systematically excluded the communities I work with. Many are only now beginning to understand how deeply harmful these policies are.

At the same time, we are witnessing increasing dehumanisation. That is why, for me, part of the work of reparation in the anti-colonial struggle is the idea that Joy itself is radical. These systems take away what it means to be human, to connect, to live with joy. Through my mandate, I wanted to restore dignity everywhere, because violations of the right to health deprive people of their dignity, to the point of genocide. My goal was to make visible what is made invisible, to amplify what is ignored. People are not voiceless or powerless – it is the system that chooses not to see or hear them.

Matilde De Cooman: Your term as UN Special Rapporteur on the right to health will end in 2026. How do you think you will look back on this period?

Dr Tlaleng Mofokeng: As my six-year term draws to a close, I feel that I have given everything I could, and I am proud of that. But every term must come to an end so that new things can emerge, and I eagerly await what comes next.

I have always been an activist; I have always belonged on the streets. So part of these six years has been about learning moderation and decorum. And that has value. There is a time and place for everything. But now I am looking forward to being myself again and returning to the streets. The streets are calling me.

Matilde De Cooman: Thank you, Dr Mofokeng, for your powerful words and your unwavering dedication to advancing access to health and human rights for all. Your work reminds us of the importance of collectively challenging power structures that undermine dignity, and of placing health workers at the centre as defenders of the right to health.